Continuing our series on the Albert Gallatin Collection in the IHR library, this post explores a few interesting items relating to the often fraught relationship between the US and Canada in the early nineteenth century. Throughout his later political career, Gallatin worked towards the peaceable resolution of the Northeastern Boundary Dispute (1783-1842) between the US and the British Canadian colonies. The first set of sources discussed here, a series of fourteen pamphlets and five maps collected by Gallatin, bear interesting provenance indicating that Gallatin relied upon a large international network of correspondents in order to flesh out his own position on the border question. The second source examined is interesting primarily for its provenance. It is a pamphlet on Canadian currency and the Bank of Upper Canada sent to Gallatin by the future first Mayor of Toronto and rebel leader William Lyon Mackenzie. All of these sources came to the IHR as the result of bequest in the 1930s by Sir Martin Conway. They likely passed into Conway’s possession through his father-in-law, the New York newspaper magnate Manton Marble. For a short time, a few of Gallatin’s books will be on display in the exhibition case in the newly refurbished Foyle Special Collections Room at the IHR.

Albert Gallatin and the Northeastern Boundary Dispute

Gallatin first became interested in the dispute between the United States and British Canada over the Maine border shortly after his arrival in Boston during the closing years of the War for American Independence. Over the winter of 1780/81 he served in the garrison guarding the coastal Maine frontier town of Machias against a possible British Invasion from Nova Scotia. He later became directly involved in the negotiations over the boundary when he took office as the US Minister to Great Britain in 1826. He continued to conduct research on the subject when he returned to America in 1827. This research culminated in the publication of ‘A memoir of the north-eastern boundary’ (New York, 1843), a work commemorating the final establishment of a permanent border under the terms of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty.

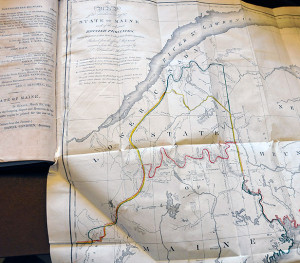

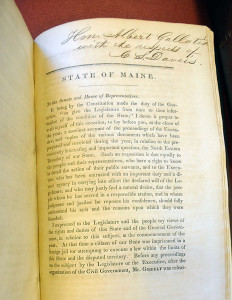

Two pamphlets in the collection bear provenance that suggest they once belonged to Gallatin. The inscription found on both of these works reads ‘[To the] Hon. Albert Gallatin with the respects of C. S. Daveis’. The man who presented these pamphlets to Gallatin, Charles Stewart Daveis (1788-1865), was a Bowdoin trained lawyer and a central figure in the development of the legal position of the United States during the boundary negotiations. Daveis served as an agent (1825-1827) for the proprietors of disputed lands in northern Maine before becoming a United States agent to the Netherlands in 1829. From the 1820s through the 1840s the state legislature published reports derived from Daveis’s research on northern land grants and settlement claims extending back to the reign of William and Mary in order to bolster American claims to land ownership. Daveis arrived in the Netherlands at a crucial moment in the on-going dispute over the international border. On the eve of the 5th federal census in 1830 the Maine Legislature sent representatives to the contested lands along the Saint John River in order to gauge popular support for Maine’s case and, perhaps more importantly, the size of the American communities in the north. The legislature hoped that residents in the disputed area might be counted in the census and that the state might therefore see increased representation in Congress. The authorities in Halifax responded by sending the New Brunswick militia to the region in order to disrupt public meetings organized by the Maine representatives. As a result of the ‘Crisis of 1830’ the US activated the clause of the treaty of Ghent (1815) that stipulated that a ‘neutral third party’ should arbitrate future border disputes between the US and the UK. Both countries agreed that King William I of the Netherlands would serve as the chosen arbitrator. Daveis, who had been sent to the Netherlands perhaps in anticipation of this development, was therefore well placed at the heart of the negotiations over the future of the border. William did not arbitrate in favour of either side’s position, instead suggesting in January 1831 that a line be drawn approximately halfway between the two proposed borders. Britain accepted the Dutch position while the US rejected it. The dispute therefore rumbled on for a further decade until the Webster-Ashburton Treaty (1842) finally established a permanent border.

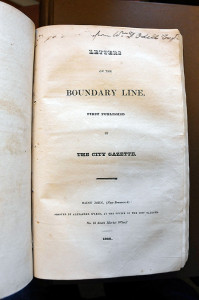

One of the pamphlets in the collection reflects the Canadian perspective on the issue and indicates that Gallatin had access to a wide array of sources and viewpoints on the issue. The pamphlet, written by Ward Chipman (1787-1851), a prominent New Brunswick judge, and entitled Letters on the Boundary Line, first published in the City Gazette (Saint John [New Brunswick], 1828), bears the inscription ‘from Wm. F. Odell Esqr’ on its titlepage. William Franklin Odell (1774-1844) was a member of a prominent New Jersey loyalist family that had settled in New Brunswick following the War of American Independence. His father Jonathan Odell was a Church of England clergyman and poet who became a leading propagandist for the Crown in New York during the Revolution. William was named after his father’s patron, William Franklin, the last Royal governor of New Jersey and son of famed American intellectual and statesman Benjamin Franklin. Odell held a number of important offices in New Brunswick over the course of the forty-year dispute. In 1815 he was sworn in as a member of the colonial legislature and in 1833 became a member of the powerful five-man Executive Council. From 1818 until 1820 Odell led annual survey missions to the banks of the Saint John in the expectation that their findings would refute American claims to the region. His final report on the topography of the borderlands was dismissed by Washington because it ignored a hilly region (the Notre Dame Mountains) near the St. Lawrence that the Americans contended was the natural boundary between Canada and the United States. The existence of these highlands mattered as the American claim to the contested region was based upon the assertion that all land encompassing the headwaters of the St. John and its tributaries flowing into the Atlantic Ocean, rather than the St. Lawrence, constituted US territory.

One of the pamphlets in the collection reflects the Canadian perspective on the issue and indicates that Gallatin had access to a wide array of sources and viewpoints on the issue. The pamphlet, written by Ward Chipman (1787-1851), a prominent New Brunswick judge, and entitled Letters on the Boundary Line, first published in the City Gazette (Saint John [New Brunswick], 1828), bears the inscription ‘from Wm. F. Odell Esqr’ on its titlepage. William Franklin Odell (1774-1844) was a member of a prominent New Jersey loyalist family that had settled in New Brunswick following the War of American Independence. His father Jonathan Odell was a Church of England clergyman and poet who became a leading propagandist for the Crown in New York during the Revolution. William was named after his father’s patron, William Franklin, the last Royal governor of New Jersey and son of famed American intellectual and statesman Benjamin Franklin. Odell held a number of important offices in New Brunswick over the course of the forty-year dispute. In 1815 he was sworn in as a member of the colonial legislature and in 1833 became a member of the powerful five-man Executive Council. From 1818 until 1820 Odell led annual survey missions to the banks of the Saint John in the expectation that their findings would refute American claims to the region. His final report on the topography of the borderlands was dismissed by Washington because it ignored a hilly region (the Notre Dame Mountains) near the St. Lawrence that the Americans contended was the natural boundary between Canada and the United States. The existence of these highlands mattered as the American claim to the contested region was based upon the assertion that all land encompassing the headwaters of the St. John and its tributaries flowing into the Atlantic Ocean, rather than the St. Lawrence, constituted US territory.

Other sources on the Northeastern Boundary Dispute in the IHR Library

- The IHR holds another pamphlet about the Northeastern Boundary dispute written from the British/Canadian perspective. The essay, written by Sir George Head and entitled ‘Remarks on the north-eastern boundary question’, was published in 1838 alongside a travel narrative recalling the author’s journey through the Canadas during the late 1820s.

- In 1839 the British government sent George William Featherstonhaugh (1780-1866) to the Maine frontier in order to finally settle the border dispute. Both sides approved of Featherstonhaugh’s appointment to the post of commissioner. He had previously worked for the US government on a number of surveying missions. Indeed, Featherstonhaugh had spent the previous thirty years in the United States, during which time he had served as the US geologist tasked with exploring the Louisiana Purchase. The IHR holds a copy of Featherstonhaugh’s journals composed during his mission on the Maine/Canadian border.

- We also own a copy of Featherstonhaugh’s published thoughts on the final draft of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, Observations upon the Treaty of Washington, signed August 9, 1842.

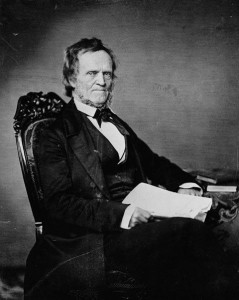

Gallatin and William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie (1795-1861) was one of the most colourful figures in nineteenth-century Canadian history. Over the course of his heavily mythologized career he was a firebrand journalist, radical politician, rebel and exile. Throughout the mid-1820s he edited several reformist newspapers, including The Colonial Advocate, which became conduits for criticism of the Canadian Tory establishment. Mackenzie directed his most scathing printed attacks towards the small group of office holders derisively labelled the ‘Family Compact’. His publishing activities earned him the ire of the Compact’s supporters who in 1826, in what is known as the ‘Types Riot’, attacked the offices of the Advocate, destroyed Mackenzie’s presses and threw his type into Lake Ontario. Mackenzie was able to capitalise upon this event through the publicity generated by the trial that followed and in 1827 he was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada. He served in the legislature until 1834 before becoming the first mayor of the newly incorporated city of Toronto.

Mackenzie is perhaps best remembered for leading the failed Upper Canada Rebellion (1837-38), in which a hastily organized group of American settlers and reform supporters attempted to establish an independent Canadian Republic. Mackenzie and his supporters hope to take advantage of the fact that the British Army regiments stationed locally had been called away to supress another rising in Quebec – the Lower Canada Rebellion led by Louis-Joseph Papineau. In December 1837, the rebel force was repulsed on the outskirts of Toronto during the battle of Montogmery’s Tavern. Afterwards, Mackenzie and other prominent rebels fled to Navy Island on the Niagara River. There Mackenzie declared himself the head of the provisional government of the Republic of Canada. The Republic was short lived and the arrival of the Royal Navy on 14 of January 1838 scattered the remaining rebels and forced Mackenzie into exile in the United States. Mackenzie landed on his feet in the US where he worked as newspaper correspondent for the next eleven years. In 1849 he was invited back to his home country as part of an amnesty agreement that followed the electoral victory of the Reformers in the 1848 legislative election. Remarkably, Mackenzie successfully transitioned back into a political career shortly after his homecoming. Between 1851 and 1858 he served as a member of the provincial parliament where he continued to pursue his quest for constitutional reform. In the last years of his life he advocated the annexation of Canada by the United States. Mackenzie died in Toronto on 26 August 1861 at the age of 66. It would seem, however, that neither sedition nor death could keep Mackenzie out of Canadian politics. He was resurrected in a popular satirical twitter feed during the 2010 Toronto mayoral election in which he bemoaned the rise of the controversial current mayor of Toronto.

The IHR Library has recently uncovered an item in our collections that bears provenance linking it to both William Lyon Mackenzie and Albert Gallatin. The item in question is a select committee report on the currency of Upper Canada published by the legislature in 1830. Mackenzie was then serving his first term in the legislature and had chaired the committee that produced this pamphlet. Mackenzie distrusted the Bank of Upper Canada, viewing it as a monopoly overseen by British office holders. Mackenzie favoured introducing hard specie in the colony and had organized the committee to investigate the feasibility of doing so. Albert Gallatin had by 1830 reversed his opposition to a national bank in the US and was instrumental in the founding of the Second Bank of the United States. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that Mackenzie would have established contact with Gallatin in order to discuss the reform position on the bank and currency in Canada. The inscription on this pamphlet in the IHR library reads, ‘To the Honourable Albert Gallatin, New York. York, Upper Canada, June 26, 1830. With W.L. Mackenzie’s Compliments.’.

Next week we will move our discussion over to the SHL library blog for the final post in the series. We will take a look at a few of Gallatin’s pamphlets held in Senate House Library’s special collections. These pamphlets touch upon many subjects including the debate over Jeffersonian political economy, ante-bellum finance and popular politics in the early American republic.