From time to time the IHR research seminars not only provide up-to-the-minute research in the History profession, but also find a relevance that goes beyond the profession and focuses on events that are happening in the world right now. One such occasion is the London 2012 Olympics. Three seminars over the course of the last two years have focused on the summer games two of which provide alternative viewpoints on the potential of legacy.

Representing the Olympics at Stockton-On-Tees (June 2012)

“Legacy” is certainly a word that has been thrown around quite regularly in the lead up to the games and has become quite a political buzzword. At times it feels like any kind of meaningful legacy will be lost and squandered due to the down turn of the economy and recession, at other times a more optimistic view prevails. There are, of course, the obvious improvements to east London, where the stadium, parks and transport connections have vastly improved. Then there is the focus on youth where attempts have been made to inspire and encourage sport and exercise. Then there are the background financial benefits of hosting the games. Numerous contracts have brought money to Britain in preparation and for the Games themselves. Whether these benefits outweigh the negatives only time will tell.

Back in November 2010, Professor Michael Collins (University of Gloucestershire) certainly had concerns that the current and previous governments of the UK have failed to come up with a truly lasting legacy. In his paper From “Sport for Good” to “Sport for Sport’s Sake”: Reversing into the Past for the Sport and Leisure History seminar, Collins argued that the 2008-11 strategy for Sport England was a backward step made worse by coalition budget cuts. Collins believes that the ambitious targets designed to attract more British citizens to sport does not fit the available budget or the actual activities of government. Whilst the 2012 Olympics has the capacity to have a positive effect on the nation’s health, Collins suggests that once over it is unlikely to have the desired long term benefit due to overambitious and poorly funded policies.

The archival legacy looks brighter however, as described by Cathy Williams (The National Archive) in February this  year. In a paper presented to the Archives & Society seminar on the topic of The Olympics, documentation strategy and the Minnesota Method, Williams described the complex task that the National Archives was confronted with in order to record and capture a one off event such as the Olympic Games.

year. In a paper presented to the Archives & Society seminar on the topic of The Olympics, documentation strategy and the Minnesota Method, Williams described the complex task that the National Archives was confronted with in order to record and capture a one off event such as the Olympic Games.

The mass of text, images, video, audio, and objects that have been created in preparing for and promoting the Olympics is staggering. Archivists at the National Archives in Kew alongside the now-defunct Museums, Libraries and Archives council (MLA) have been developing frameworks, making or extending connections with businesses, government, charities and other bodies with some form of involvement in the event not only from when the bid became successful, but from the very moment (or as near to as possible) that the idea of bidding for the 2012 Olympics was written down. Thus archivists have been dealing with the Olympic archival legacy for at least a decade.

The documentation strategy employed to capture the London Olympics for future generations is simply called The Record and attempts to capture as much multimedia information and experiences related to the Olympic Games as possible from the inception of the idea to bid for the games, right through the bidding process and lead up, and finally the Games themselves. The data collected, as with all archival collections, had to be decided upon and gathered in relation to various organisations and groups. At the heart of any collection are a series of decisions and concessions concerning content, data management, and access. A good or bad decision early on in the process can make all the difference as to the success or failure of a collection.

In the case of the Olympics the National Archive and MLA were faced with a difficult problem: how do you capture the delivery, managing, and enjoyment of a finite event? Where is your starting point and where do you stop? Cathy Williams explains that in this instance the Minnesota method was employed as a framework for drawing in material to the archive: they were interested not just in what they might normally expect an archive to contain, but on what they might normally have missed. The Minnesota method is basically an archival strategy for appraising materials that combine aspects of collection analysis, documentation strategy, appraisal, and functional analysis. The method attempts to enable archivists to find not only the obvious materials but those that might be less obvious. Cathy Williams notes that there are relatively few examples where the Minnesota method has been employed in its entirety but the challenge of the London Olympics will become one of them.

The result is the National Archives Olympics website The Olympic Record. This site is usefully split into two: one option takes you to a beautifully displayed timeline containing archival materials from the first modern games of 1896 (held in Athens) right up to the London 2012 games. The other option ‘2012 Activities’ brings you straight to the archival collection undertaken by the National Archives and MLA which is already looking like an amazing resource.

I think what is most exciting about this venture is that even when these Olympics are done and dusted, the legacy of the archives continues not only as a collection in its own right but as a way forward for future Olympiad events. Cathy Williams explained that the process they undertook in developing a strategy for archiving the Games will be handed over to the next host nation and then the next. The archives for the London Games will therefore be placed within its wider context of the Games history forming part of a much larger and fascinating collection about sportsmanship, competition, and even organisation on a global scale. The Olympic Record website supports this aim splendidly and is well worth a good delve.

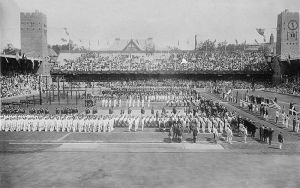

One of the Olympic Games recorded on this site is the 1912 games that were held in Stockholm. In another of the podcasts retained in History SPOT Dr David Day (Manchester Metropolitan University) looked at the developing role of the professional trainer in 1912 and how that development was looked upon by athletes in Britain and America in-particular. This session was called ‘A Man Cannot see his own faults’: British Professional Trainers and the 1912 Olympics.

The development of professional trainers in America was considered bad play in Britain, where Gentlemen sportsmen saw fair play, participation and volunteerism as essential attributes and what the games should all be about. However, as Day argues, the picture in Britain was not quite that clear cut. Although monetary gain was kept to a minimum many amateur athletes and indeed the Olympic committee for Britain sought the aid of high profile amateur and professional coaches and trainers. Slowly the desire to focus on taking part over winning was to fade as the desire to win and advance increased with recognition that professional trainers could improve athletic ability.

The 1912 Olympics held in Stockholm saw the participation of just 28 nations and 2,508 competitors (of which only 48 were women). There were almost half the games of the 2012 Olympics available (14 sports in all broken down to 102 events). The games saw the debut of Japan and thus represented the first time all five continents participated. This was also the first time that the modern pentathlon, women’s swimming and women’s diving became a fixture of the event. There was, as yet, no Paralympics (that would not be introduced until 1960 although an International Wheelchair Games has been held since 1948). Modernisation was rife in other areas too; this was the first time that automatic timing devices were used for track events as well as the photo finish and public address system.

Links to History SPOT podcasts:

Sports and leisure History Seminar 8 November 2010 Professor Michael Collins (University of Gloucestershire) From ‘Sport for Good’ to ‘Sport for Sport’s Sake’: Reversing into the Past Sport History 6 February 2012 Dr David Day (Manchester Metropolitan University) ‘A Man Cannot see his own faults’: British Professional Trainers and the 1912 Olympics Archives & Society 21 February 2012 Cathy Williams (The National Archive) The Olympics, documentation strategy and the Minnesota Method