This post has kindly been written for us by Catherine Arnold, Mellon Dissertation Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research.

When does a state’s treatment of its subjects warrant foreign intervention? As we do today, men and women in early eighteenth-century Europe struggled to answer this question. Throughout this period the British government received formal and informal petitions for aid from religious minorities across Europe. And, in many cases, British officials responded. Between the 1690s and the 1710s, British diplomats negotiated international treaties that guaranteed rights—including liberty of conscience—for Protestants residing in Catholic states. From the mid-1710s, British ministers also instructed diplomats to petition European rulers for redress of the grievances of non-Protestant minorities or granted these groups asylum in Britain and its empire. By the 1740s, British diplomats had interceded on behalf of Jansenists in France and Jews in Portugal, Bohemia and Moravia. In my dissertation I seek to explain why this was so. Why did the British government begin to intervene on behalf of Catholic and Jewish communities—while also negotiating on behalf of Protestant minorities—between the 1690s and the 1740s?

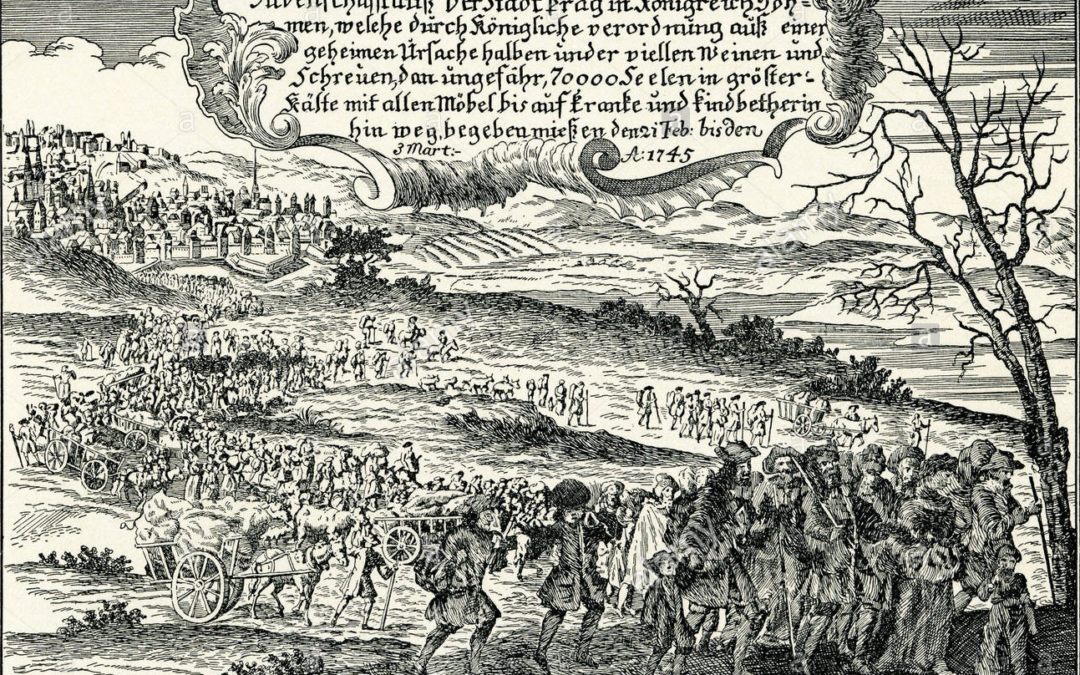

In 1745, the British ministry responded to a transnational lobbying campaign and interceded with the Queen of Hungary, Maria Theresa, in an effort to halt the expulsion of Ashkenazi Jews from Bohemia. This print, titled “Exodus of the Jews from Prague, 1745,” and published in the same year, shows the Jewish community of Prague leaving the city. See: http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12329-prague

To answer this question, I’ve chosen to examine the British government’s interventions on behalf of five minority communities during the early eighteenth century: Huguenots, or French Protestants, in France and on the Continent; Vaudois, or Reformed Protestants, in the duchy of Savoy, in northern Italy; Jansenists in France; and Jews in Portugal and in the territories of the Habsburg monarchy, Bohemia and Moravia, in the present-day Czech Republic. I argue that British politicians’ negotiations on behalf of Protestant and non-Protestant minorities between the 1690s and the 1740s were, in large part, the result of extra-governmental diplomacy and lobbying. Protestant and non-Protestant minorities coordinated transnational lobbying campaigns intended to convince European governments, like Britain’s, to maintain their privileges and protect them against repressive policies.

In making the case for intervention, lobbyists, propagandists, diplomats and politicians in Britain and on the Continent frequently characterized government interventions as charitable projects and justified them on moral grounds. Minorities were often referred to as “objects of charity” rather than as Lutherans, Calvinists, Catholics, or Jews. Although justifications for intervention predicated on “compassion to those poor People,” as one of the British Secretaries of State put it in 1745, had sixteenth- and seventeenth-century antecedents, my research suggests that, during the early eighteenth century, these justifications were invoked with greater regularity. What’s more, these arguments were used to justify the British government’s intercessions on behalf of non-Protestant minorities, including Jansenists and Jews.

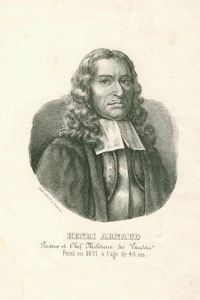

Henri Arnaud (above) was a pastor of the Vaudois church. In 1699, when the Vaudois were forced to convert to Catholicism or leave the duchy of Savoy, Arnaud was deputized to lobby the English government for aid. See http://www.huguenot-museum-germany.com/huguenots/galleries/huguenot-portraits/a-b/arnaud-henri-1.php

How did these ‘objects of charity’ plead their cases to Britain, as well as to other European states? In my research so far, I’ve found that Protestant and non-Protestant minorities lobbied the British government by several routes. In some cases, a member of the community might be deputized to petition the British Secretary of State or a member of the royal family directly, either in writing or in person. In addition to this direct approach, communities arranged for influential British subjects to lobby on their behalf. To do so, deputies or other community members wrote to politicians, members of voluntary religious societies and members of early Enlightenment correspondence networks in Britain, asking them to plead their case to the British ministry. They also mobilized members of longstanding religious institutions across Europe—such as churches, consistories, and synagogues—to petition the British government in their favor. Communities even pressed other European governments to lobby Britain on their behalf. By convincing the British government’s constituents at home and its allies abroad to lobby on their behalf, while also conducting direct petitioning campaigns, minorities pressured the government to consider their appeals and intercede on their behalf.

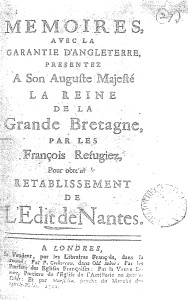

As minorities mobilized acquaintances, fellow scholars, and co-religionists across Europe to lobby on their behalf, they also put pressure on European governments, like Britain’s, by publicizing their lobbying. When they lobbied the British government, members of these communities ensured that news of their appeals for aid—and, just as importantly, the ministry’s response to those appeals—circulated among European diplomats and politicians by presenting petitions to the Secretary of State in public audiences. At the same time, lobbyists often made these audiences known to a wider reading public, in Britain and in Europe, by selling printed copies of their formal petitions. News of minority grievances was also disseminated, at times, through sermons given by sympathetic clergymen or rabbis. And, not least, British and European newspapers, reported on the treatment of these communities and on their campaigns for aid, sometimes even printing letters that described minorities’ grievances or governments’ intercessions on their behalf. The public nature of these lobbying campaigns meant that the British government risked alienating sections of public opinion at home and abroad, as well as damaging its reputation at those European courts sympathetic to minorities’ grievances, by ignoring their petitions.

An example of a formal petition that also circulated in print. In 1712, as the British government began peace talks with France at the Congress of Utrecht, French Protestant “Refugees” in Britain asked the British ministry to insist that Louis XIV restore the Edict of Nantes, which had granted limited rights to French Protestants. Their petition and its accompanying memoranda (shown above) were printed and sold by French Protestant booksellers in London. Memoires, avec la garantie d’Angleterre, Presentez a son auguste Majesté la reine de la Grande Bretagne, par les François refugiez, pour obtent retablissement de l’edit de nantes. Londres, 1712. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Gale. Yale University Library. 27 Apr. 2015

So why do these cases matter? My research suggests that, during the early eighteenth century, intercessions and lobbying constituted an increasingly differentiated sphere of international politics, one in which informal lobbying and private negotiating coexisted with, and gave direction to, governments’ formal diplomacy and policy-making on the issue of how to treat foreign minorities. On this issue, members of civil society and religious personnel from across Europe could influence British foreign policy and diplomacy through their lobbying. And, I believe, the same argument could be made for other European governments. I’ve found evidence that France, the Netherlands, the Evangelical Swiss Cantons, the Republic of Geneva, Prussia, Sweden, some German principalities, Portugal, Spain, and the Habsburg monarchy were involved in negotiations about minority communities in their own or in other states’ territories during the early eighteenth century. Over the next eight months, I will visit archives in Italy, Geneva, the Netherlands, and France to develop this argument further. At the moment, though, I argue that through these lobbying campaigns and state interventions questions of minorities’ civil and religious rights, repatriation, and asylum gradually became a part of early eighteenth-century international politics.

It’s been argued that the experience of the seventeenth-century confessional conflicts led to the emergence of the modern state system, founded on the principles of state sovereignty and nonintervention, during the late seventeenth century. My research indicates that although confessional military interventions ceased during this period – Protestant governments no longer formed leagues to defend their faith, for instance – states did continue to intervene in each other’s internal affairs. By the early eighteenth century, politicians in Britain and on the Continent had begun to undertake a type of diplomatic intervention, which was intended to protect minorities’ rights and justified on moral grounds. Transnational non-governmental organizations, including religious institutions, played a significant role in this transformation. Well before the so-called ‘humanitarian revolution’ of the later eighteenth century politicians, clergymen, and members of civil society across Europe debated whether foreign governments like Britain’s should aid repressed religious minorities in other states. By further exploring these interventions I hope to offer a new perspective on the development of modern international relations and elucidate the emergence of an international politics centered on humanitarian concerns.