My previous post on the range of history material being published opened with the early modern view of masculinity and men crying. Go back a couple of hundred years and it seems men were allowed to cry, and at least if you were a bishop, the act was deemed appropriate, usually in a religious sense, and of course if the crying was not seen as too ostentatious. As observed in Episcopal emotions: tears in the life of the medieval bishop, by Katherine Harvey, the significance of weeping in the life of the late medieval English bishop was key to perceptions of his masculinity, his sexuality as well as his physical body. Furthermore, the act had significant implications for his reputation both as a cleric and as a potential saint.

Of course not all prelates were prone to weepy emotions. In The political and military agency of ecclesiastical leaders in Anglo-Norman England: 1066-1154, the role of ecclesiastical lords in the Anarchy is discussed. Such bishops became despoilers of the countryside. Indeed one chronicler argued that bishops were behaving in much the same fashion as secular lords in warfare, carrying swords and wearing armour.

A local history view of the Anarchy can be gleaned from Edmund King’s King Stephen and the Empress Matilda: the view from Northampton where the civil war led to conflict over land and lordship especially for Simon de Senlis, earl of Northampton.

Returning to the weeping theme, Stephen Spencer, in The emotional rhetoric of crusader spirituality in the narratives of the First Crusade, analyses representations of fear and weeping in the Latin narratives and argues that emotional displays functioned as markers of crusader spirituality (rather like the weeping bishops above). He then explores depictions of weeping as an expression of piety, focusing specifically on tears shed over Jerusalem.

If you are interested in further tear duct activity, I’d recommend Crying in the middle ages: tears of history, which looks at the role of tears in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic cultural discourses covering the arts, preaching, literature (including Piers Plowman), and in the emotion of pilgrimage.

I’d also recommend the History of Emotions blog.

On a completely different theme, I was intrigued by two war-related articles. The first discusses Quaker peace activities prior to the World War I – “Edwardian peace testimony: British Quakers against militarism and conscription c. 1902-1914”, in Journal of the Friends Historical Society, 2010, vol. 61:1 p. 49-66. The second, Human Computing Practices and Patronage: Antiaircraft Ballistics and Tidal Calculations in First World War Britain, outlines the importance of mathematics and the work of Arthur Thomas Doodson, an intriguing scientific aspect of the conflict. As one can imagine a great deal has been written on the Great War largely in special issues of journals, indeed so much has been written I plan a blog covering those issues.

There are two articles, both animal related, which vie for best title. A “Bovine Glamour Girl”: Borden Milk, Elsie the Cow, and the Convergence of Technology, Animals, and Gender at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, by Anna Thompson Hajdik, looks at the adoption and development of the company’s popular and eponymous mascot.

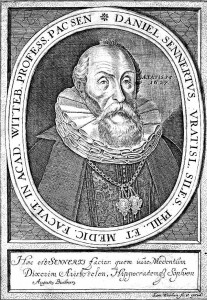

Joel Klein’s article, Daniel Sennert, The Philosophical Hen, and The Epistolary Quest for a (Nearly-)Universal Medicine surveys Sennert’s pursuit of nearly universal medicines made from noble metals. One of his experiments involved feeding a hen silver or gold during favourable astrological conjunctions.

As usual all relevant material will appear in the Bibliography of British and Irish History.